Arts for the Built Environment

CONTENTS

BACKGROUND

CONTEXT

FINDINGS

LEARNING AND RECOMMENDATIONS

QUESTIONS AND TALKING POINTS

WHAT NEXT?

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & THANKS

BACKGROUND

In 2024 I travelled to Colombia and Mexico to research the role and impact of grassroots community arts in creating positive social change for my Churchill Fellowship. I wanted to learn about best practice for setting up, developing and supporting community arts projects and processes, particularly in “ignored spaces”, in areas where people have not previously had much access to art and places where people have limited resources. I was interested in exploring whether there are any advantages to community activism taking place in such unpoliced, informal or “loose” spaces. I also wanted to see how communities engaged people and retained those connections and explore any advantages and disadvantages to community processes done from the bottom-up as opposed to the top-down structure more common in the UK. The word grassroots (or equivalent) is not commonly used in most of Latin America as most community work is done for communities, by those same communities, so it is taken as a given that it is “grassroots”, or done from the community at base level. In the UK it is more common for governing bodies, charities and organisations to instigate and carry out community projects and so decisions are often made from outside that community.

Through meeting with groups and individuals who have created impressive and huge positive social change through their creative work, I am learning how I might improve my work as a socially engaged practitioner in the UK. I work with community groups from many different backgrounds including young people, older people with dementia, people at risk of homelessness, refugees and asylum seekers, vulnerable women, people with learning disabilities, intergenerational groups, mental health organisations and more.

CONTEXT

Clearly there are many cultural, political and social differences between Colombia and Mexico and the UK and it is an ongoing and fascinating process to see how learnings from Latin America will translate to the UK, taking the successes from there but adapting them to work in a different country.

Many areas of Mexico and Colombia have experienced violence, political and social instability and historical absence of state support in a way not felt in much of the UK. Yet in the neighbourhoods I visited, where people have had to endure deep trauma, often with very few economic resources, they are themselves creating outstanding transformations through grassroots community projects. For example, in Charco Azul, Cali, Colombia, community peace projects and strategies helped to reduce the number of murders by 47% in two years. Asociación Mejorando Vidas (Asomevid) is a social organisation which works to improve lives in Charco Azul. One of its most notable campaigns was “Yo Soy El Presidente” (“I Am the President”) where the community encouraged everyone to take responsibility for the issues within it and young people were supported to stand for local elections, win seats and become more empowered and connected. Asomevid also worked tirelessly to regain the trust of younger people, which helped deal with problems of apathy.

Something I was very interested to explore was whether trauma and lack of state support can push people to form tighter and more active communities and what we can learn from that. I wanted to look to at whether some places which are more informal and less controlled and policed, while perhaps being more potentially lawless and dangerous, can also be more open to change in how that space is used.

I looked at how people use public spaces to relax, protest, express themselves socially and politically, communicate, share, buy and sell, create, experiment and celebrate; I explored any differences between Mexico, Colombia and the UK.

FINDINGS

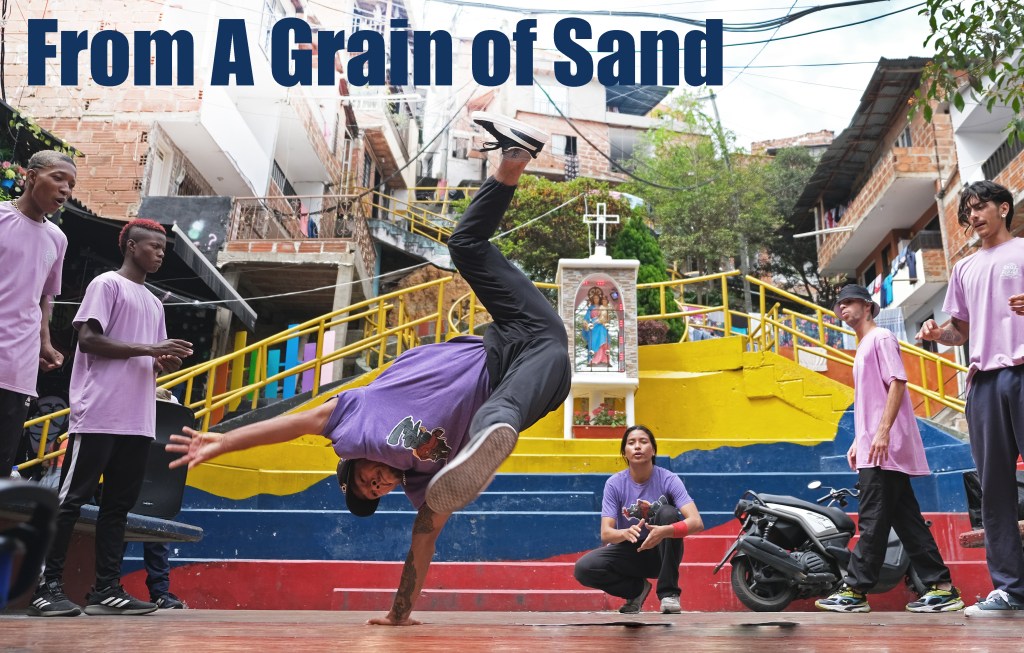

For the Colombia element of the Fellowship I have made a film From A Grain Of Sand which can be seen here: https://youtu.be/foXcjOekJ1E

The film contains interviews with various artists and organisations working to have a positive impact on their communities.

There are also a number of photographic blogs written while I was away which can be seen here: https://www.instagram.com/laura_page_photography/

LEARNING AND RECOMMENDATIONS

Ignored spaces

Places which experience a lack of state intervention, primarily deprived neighbourhoods, tend to have many spaces which can potentially be taken over because fewer people want to use them. The advantage of this can be free space for diverse community events or actions with the knock-on effect of transforming space so that it continues to be used for something more positive.

Street artists in Medellin, Colombia, told me how, once they’d painted walls, they saw a change in how the community used that space. Where it was once used for drug dealing it began to be used as a space for picnics and family birthday parties. In Cali, Colombia, a community designed and installed children’s play equipment in a high crime area so not only did the criminals move out but children played there and festivals and dancing started to happen there, which in turn encouraged small enterprises to operate in that space and also more people from outside to visit. In many cases people told me that once the government saw that the community were transforming themselves they offered help such as improving transport links for the community.

- Recommendation

If communities are given freedom, support and resources to transform areas which are unused or used for negative purposes then not only the process but the knock-on effects can be profound. This help should be offered by government, councils and organisations.

In the UK, where many of our remaining youth and community centres are closing, it is still important to have a safe space for people to go. Public places such as churches, libraries and disused buildings could offer important space for communities to gather, offering free access for more varying activities and at different times. Grassroots community work may be more successful when the places and people offering space and time know and understand their community inside out. But if this space and time is offered for free, how do those who offer it survive? And how are they paid?

Boundaries

Architectural elements may distinguish the outside from the inside – thresholds are spaces for playful possibilities. Doorways, turnstiles, terraces, stairways and porches may mark the place between these boundaries or they may be invisible. Either way, they can be important to how space is used by a community and so their access, use and appearance should be carefully considered. In Mexico and Colombia, particularly in violent neighbourhoods, there can be invisible boundaries. These can change as gangs take ownership of different areas and crossing these invisible borders can be lethal.

In Colombia and Mexico I saw numerous instances of people opening up their own homes to communities. Having a space away from these boundaries was vital to people feeling safe.

- Recommendation

In the UK special attention should be given to how communities feel and act around their geographical boundaries, visible or otherwise. External organisations may often be completely unaware of these boundaries even though they can hold great importance for a community. In Sheffield where I work, the city is quite unique in that in some areas it is made up of many quite isolated areas sitting right next to each other where people have lived for generations and tend to stay in what they consider their patch. In some of these areas people can be daunted by going into what they consider another territory even though it is very physically close. Encouraging people to come together at these boundaries and respecting, breaking, ignoring or acknowledging them can all have consequences and this should be addressed by communities and external organisations.

Art for all by all

Mural/street art is very common in both Mexico and Colombia and often has social or political context. While the work itself is transient, the legacy can be long lasting. Unlike many kinds of art, it is accessible to all who pass it and it can be created by anyone who can afford the paint. Street artists are often people who could not afford to be traditional artists who live by exhibiting in galleries and such-like, and so a different voice is heard. As seen in Getsemani, Colombia, an area with many people with mixed and Afro-Colombian heritage, the characters depicted in the street art represent people from those communities in an aspirational and powerful way, which leaves a positive impact.

Community leaders and elders, past and present, are also often subjects of the murals reflecting and endorsing the deep respect towards them.

- Recommendation

Decision-making bodies should strongly consider allowing communities to create their own public art by passing some decision making for local spaces to them and providing adequate resources such as training, support and paint for them to do this to a high standard. Making relationships with local businesses, especially those with communnity strategies and commitments, can help to gain local agreement and provide resources.

Resources and access to art

Lack of state support in parts of Mexico and Colombia has meant people have had to offer so much of themselves, often giving a huge amount of their personal space and time to their community. While this seems an unfair struggle it can bring a sense of peace to those who do it. When forced to do things themselves people find a power, responsibility, ownership and a connection to their community, which they may not have felt otherwise. Something which can make this difficult is when there is less work or opportunities in these areas so people have little support but it can also mean people have more time to volunteer and impetus to improve life.

- Recommendation

I believe the UK would benefit from a structure where people have less pressure on them to constantly produce for people outside their community. Shorter working weeks and less onus on spending money on luxuries would give people more time to dedicate to themselves and their communities.

In the UK, which is one of the most age segregated countries in the world and with relatively small functioning family units, it seems placing devout importance on our community cohesion would benefit all. This could give projects greater longevity, authenticity and relationships of trust and deal with many of the issues of misunderstanding and abandonment that can happen when external organisations temporarily go in to work with a community, as can be more common in the UK.

Community engagement

As seen in the community garden of Moravia, Colombia, if community work is paused and goes unnurtured for some time processes can very quickly turn backwards. There is rarely a quick fix. Work must be ongoing.

- Recommendation

Support sustainable ongoing grassroots projects. External organisations parachuting into a marginalised, vulnerable community for a limited amount of time and leaving again with no strategy for sustainability does not work. It can be very damaging to communities when they feel work is being done “to” them rather than “with” them. Working with a community over a long period of time, asking what they want and need and giving them the support and resources would be a more successful approach for the UK.

Trauma, suffering and apathy

Social dialogue can be transformative, for example, state initiated talks with the Marxist-Leninist Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrillas, and the importance of listening to the testimonies of victims and honouring memories as part of the peace process. Despite issues with the peace process, the focus on territories seems to have encouraged hope and a “bottom-up” approach for transforming communities using participatory engagement.

“For grassroots organisations of diverse collectives representing long-suffering rural areas, it offered hope for material change through more equitable land and resource distribution, infrastructural investment and democratic participation, and a secure space to propose alternatives to development” (Diaz, Staples, Kanai, Lombard)1

- Recommendation

A key element in achieving healthy, safe, thriving communities in the UK has to be equality, truth and access to resources. Much of this needs to be imposed at a government level. If there is inequality and poverty at a root level because of legislation and structure it will be very difficult for a community to help themselves. The voices of marginalised individuals and communities needs to be heard, acknowledged and acted upon for real social change.

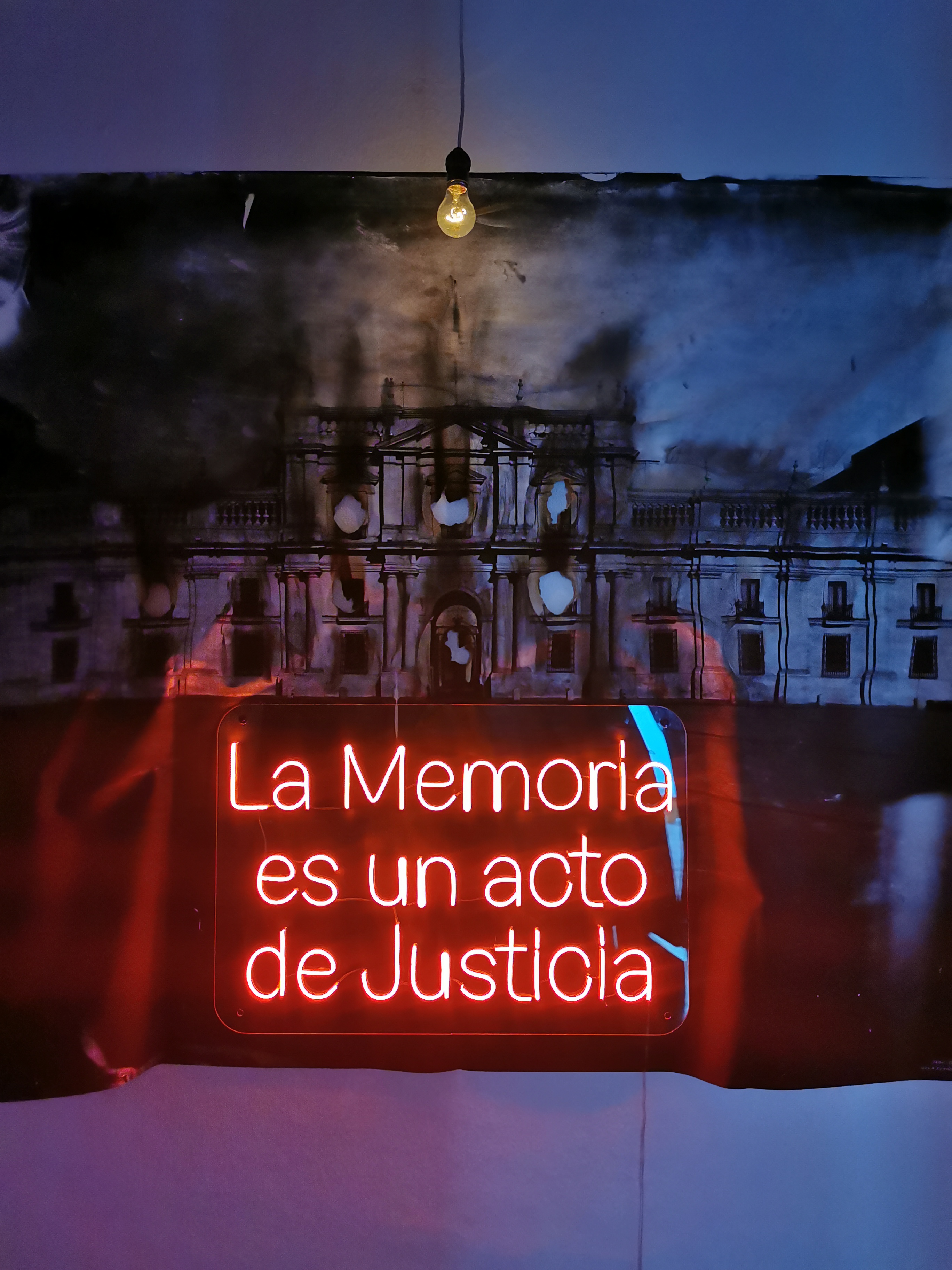

Memory and narrative

Truth is an important issue often discussed in Mexico and Colombia. When states and other groups have lied again and again about the truth of past atrocities, people are fighting to preserve the truth of what has happened to them. An example is the case of the False Positives murders in Colombia where an inquiry found that 6,402 civilians were murdered by the military and passed off as rebels in order to give the impression that it was winning its fight against the FARC guerrilla group.

Art has proved to be a very important tool in allowing people to dissect and interpret various narratives and explore memory as a construct and how it can be used to manipulate.

- Recommendation

Resources need to be put into community arts at a grassroots level allowing communities to decide how funding is spent and how it can be used to give them a voice that is empowering and true whether it is difficult for some to hear or not.

Large scale community murals celebrating elders in the way widely seen in Latin America could really benefit UK neighbourhoods helping to build relationships between age-groups, develop artistic skills, improve pride and respect within the community and boost confidence and opportunities.

Artwork in Oaxaca, Mexico which says “Memory Is An Act of Justice”

QUESTIONS AND TALKING POINTS FOR WORKSHOP DISCUSSIONS

What are the issues and the benefits of areas lacking in state intervention? How can this be used to the advantage of the community?

How can communities build trust and confidence within themselves? Does this need to begin from within?

Can bigger communal traumas enable greater community strength and power? What is the effect of long and short term community trauma on apathy? How do we harness this kind of power while avoiding the trauma?

How feasible is cultural change to empower communities in terms of norms relating to ageism, activism and ownership?

Can external funding negatively interfere with the direction a community takes?

Is there an ideal balance between grass roots community development and external support?

WHAT NEXT?

Twinning communities – I am talking with communities in Sheffield and in Colombia about them forging relationships between groups of young people where they can keep in touch using an art film dialogue to learn about one another, broaden their horizons, open self-perspective and encourage each other to push creative boundaries.

Sharing my film – I’ll share my film at various workshops and events with discussions afterwards to build upon the learning. The initial showing will form part of a fundraising event with music and food and drinks to raise money for two of the community organisations featured in the film. I have stayed in touch with one of the communities and one of the universities I worked with in Colombia and they have made a museum and photography exhibition in their community centre off the back of some photography workshops I ran with them. This may move to be shown in the city centre and the idea is that my film will be translated and shown there.

Creating large-scale community murals – Taking inspiration from the street art of Mexico and Colombia, particularly that celebrating elder community leaders, we will combine my Hidden Depths portraits challenging ageist stereotypes with new techniques to create large murals in the UK. The project will forge relationships between communities, artists, companies (such as paint companies) and councils to work together in trust to achieve ambitious and sustainable projects with great social impact. This will build upon my learning with graffiti artist RemixUno who I spent the day with in Mexico City.

Transforming “loose” spaces – in upcoming projects I will encourage communities and councils to use unpoliced and ignored spaces to their advantage as a free space to create and share.

Campaigning for grassroots bottom-up community decision-making – campaigning for a different model of funding distribution such as state support with minimal outside interference. Speaking for communities to have the resources and training they need take power and responsibility to make safe, strong, creative and connected communities.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS & THANKS

Asociacion Mejorando Vidas (ASOMEVID)

Carlos Tobar, Pontificia Universidad Javeriana – Cali

Casa B

Estudio 74

Fundacion Sondemigente

La Jefa

Manu Mural

Melanie Lombard, The University of Sheffield

Oasis Urbano

Remix Uno

The Churchill Fellowship

References:

1. Diaz, Staples, Kanai, Lombard [“Between pacification and dialogue: Critical lessons from Colombia’s territorial peace”, Published by Elsevier Ltd., 2020]

Copyright © 2024 by Laura Page. The moral right of the author has been asserted.

The views and opinions expressed in this report and its content are those of the author and

not of the Churchill Fellowship or its partners, which have no responsibility or liability for

any part of the report. All images are the author’s own unless otherwise stated.

Leave a comment